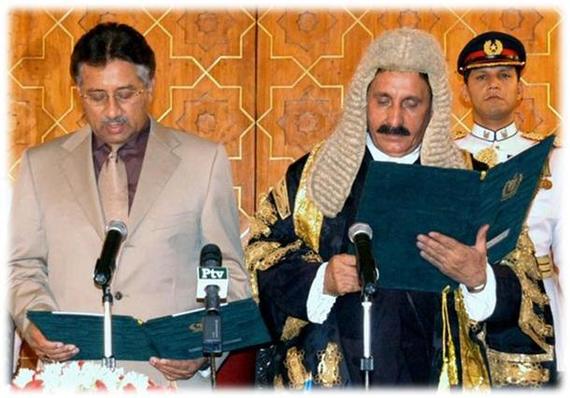

By Bilawal BhuttoPlato's philosophical discussion, the Crito, illustrates the dilemma faced by those of us who yearn for an independent judiciary in Pakistan. Too many of us had to suffer at the hands of a judiciary so independent that it often acted independently of both the basic principles of jurisprudence and the very constitution it swore to uphold and protect. Plato's Crito is a dialogue written about Socrates, who was imprisoned on trumped up charges. His friends come to him in prison, and try to convince him to escape. He refuses, stating that he had lived by the city's laws while they benefited him, he would live by these laws too even if it kills him; he could not pick and choose. His position was that one has to buy into the city and its laws in their entirety or not at all. In essence, it is ever good to respond to injustice with injustice? Can a state exist in which the law becomes optional? Shaheed Mohtarma Benazir Bhutto worked tirelessly for almost a decade, leading the fight against the military dictatorship of General Musharraf. The major instrument used to hinder the movement for the restoration of democracy was the judiciary. The courts were deployed to hound democrats by having politically motivated cases framed against them. The judiciary, in fact, suffered severe embarrassment ,when tapes emerged showing judges of the High Court receiving instructions from the Government to convict Shaheed Benazir Bhutto, and her husband Asif Ali Zardari, in these politically motivated cases. By 2007, Shaheed Benazir Bhutto's mission to restore democracy had picked up enough momentum that success seemed inevitable. With elections looming and the former Prime Minister's soaring popularity, a PPP victory was all but guaranteed; the dictator was forced to the negotiating table. One of the primary demographic support bases of the dictator was a portion of the conservative, urban middle class, who benefited from the dictator's patronage. This support base began to erode when the dictator fell out with the Chief Justice, Iftikhar Muhammad Chaudhry. The judge was sacked, violating the constitution, which stipulates that the removal of judges of the superior courts can happen only through the Supreme Judicial Council. This was a rather drastic transformation. For a judge who had originally legitimised the dictator's coup and rather extraordinarily granted him unprecedented powers to amend the constitution; a power even the dictator did not ask for. Overnight, the very same judge turned into a symbol against the general. The Lawyers' Movement pushed for the restoration of the Chief Justice. The movement was given broader support when political parties joined the movement. With the Bhutto's and her Pakistan Peoples Party's ability to gather large crowds all over Pakistan, due to its status as the country's only national and largest political party, the movement truly started to pick up steam. The PPP flags were the most numerous and visible at the Chief Justice's rallies. The PPP suffered the most casualties during the movement; the two most harrowing incidents being a bomb blast that targeted a pro-CJ rally in Islamabad, and during the infamous May 12 massacre in Karachi, where supporters of the Chief Justice were shot at by militants supporting the dictatorship. The entire time however, Bhutto was wary of the politicisation of the judges. We often had heated debates about the amount of support that should be extended to the Lawyers' Movement. She believed that, as a politician, it would be inappropriate for her to meet with these judges. She would say, "I am a politician, if the judges want to join politics and negotiate with me they should form the Judges Party and I would be happy to meet". Bhutto was completely justified for having these reservations. PPP founder, and our country's first democratically-elected Prime Minister, Shaheed Zulfikar Ali Bhutto was sentenced to death and hanged for a crime he did not commit. The court decision was, and still is, universally condemned as judicial murder. Shaheed Benazir Bhutto's husband, Asif Ali Zadari spent 11 1/2 years in prison as a political prisoner. He was finally released in 2004 after waiting 8 years to be granted bail in a case pertaining to whether he paid duty on an imported car. While the Chief Justice's recent stance against the dictator was appreciated, it did not exonerate his actions as a judge either who supported the 1999 coup of General Musharraf or who allowed the political victimisation to continue, as he was sitting on the high courts of the land. In addition, by taking up the National Reconciliation Ordinance, the Chief Justice almost sabotaged the freeing of political prisoners and the return of exiled prime ministers before the elections. Exploiting the immense public pressure, using the incentive of future co-operation as well as international pressure from the dictator's biggest supports and donors, the United States of America, Bhutto demonstrated her mastery of Real Politik by convincing Musharraf to shed his second skin and remove his military uniform. Musharraf was now an illegitimate president who no longer enjoyed absolute power, both as head of state and chief of army staff. Curiously, the Chief Justice still allowed Musharraf to reman unconstitutionally elected, and even swore him in as President following what the opposition called an illegal presidential election. However, once Musharraf imposed emergency rule and effectively launched what was dubbed a second coup , it became clear he had no intention of giving up his illegal power. The Chief Justice and his fellow judges were placed under house arrest, and the Lawyers' Movement was fully embraced by the PPP, despite its prior principled reservations. On December 27th 2007, Shaheed Benazir Bhutto was assassinated. Subsequently the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) won the elections, formed government and freed the judges. Under threat of impeachment, Musharraf resigned and fled the country. However, the newly-elected Government faced a quandary. How would it restore the former Chief Justice without setting the precedent that a government could sack and replace a sitting chief justice? In addition how were they to get around the fact that the former Chief Justice had been politicised? How, for example, would the restored Chief Justice hear cases from lawyers who lead the movement to give him his job back? The Lawyers' Movement did not acknowledge these complexities and continued with the same tactics against the democratic government that they had used against the dictator. Despite immense public pressure, the PPP Government held its ground and only restored the former Chief Justice once the sitting Chief Justice retired. It started to become clear, almost immediately, that the Chief Justice was not interested in any greater ideals of justice, rule of law and democracy, but unfortunately was in fact hostage to his own personal vendettas. Those of us who had suffered at the hands of the biased judiciary had high hopes of finally receiving justice. But to no avail. In his first major decision after his restoration, the Chief Justice did exactly what the Lawyers' Movement were protesting against; he did not abide by the constitution. He did this by not referring the case of the PCO judges who had not resigned with him in solidarity, or the new appointments, to the Supreme Judicial Council. And instead, with the stroke of a pen, the newly restored judges expelled judges opposing them from the court. In the run up to the election the two major political parties had signed the charter of democracy, in which they had agreed on judicial reforms. One of these reforms was to improve the manner by which judges were appointed. The prevailing process at that time allowed judges to appoint other judges with no binding input from either Parliament or the Executive. The new, democratically-elected Government unanimously passed the 18th Constitutional Amendment. Through this, a parliamentary committee was set up with representatives from every political party in Parliament, along with retired judges and renowned lawyers, that would appoint judges to the courts. The Chief Justice first exerted extraordinary pressure on the parliament, by threatening to strike down the 18th Amendment, and, as a result, to make the changes he desired and pass a 19th amendment. The pressure resulted in the consequent 19th Amendment, which allowed more judges to be involved in the committee. In spirit of good will, we complied and passed the 19th Amendment. However, in a matter of months, the Chief Justice, through court rulings, hollowed out the committee, effectively making it powerless and keeping the appointment powers with himself. Thus he returned us to a system of appointment that was of the judges, by the judges and for the judges. Delay in justice, inefficiency and corruption of judges was seen as major reason for the eroding of the writ of the sate, and increase in support for illegal tribal courts, and even Taliban shuras. All judicial reforms aimed at addressing these issues were aggressively resisted by the CJ. In fact, the judicial system overall has been steadily degraded, debilitated and dissembled. By removing judges who disagreed with him from the court, the number of judges in the country effectively halved overnight. In addition, a system contrived upon the excessive use of suo motu powers to pick up cases, was abused; populist issues drawn from our sensationalist cable television shows, and even from conservative newspaper editorials, increased the courts' work load and further hampered the efficiency of the judiciary. During the term of this Chief Justice, Pakistan saw a massive expansion of judicial overreach, hyper-judicial activism and frankly a quasi-judicial-dictatorship. This resulted in a situation where the courts frequently interfered in domains in which they had no constitutional jurisdiction; namely, the Parliament and the Executive. The courts hampered the Government's economic policies by intervening in the pricing of commodities and reduction in subsidies, to which the GOP had agreed, in order to acquire a loan from the IMF. The Supreme Court, under CJ Iftikhar Muhammad Chaudhry, regularly interfered in matters of public policy; for example, ordering the Government to slash sugar, flour and gas prices at different times. It started when the CJ/SC declared privatization of the steel mills as void and illegal. In 2010, the SC interfered to effectively strike down LNG (Liquefied Natural Gas) contracts. Post restoration, the SC's interference in economic matters has progressively increased in scope and intensity. In the RPP (Rental Power Plant) case, the SC went a step further. Whereas in the Steel Mills and LNG cases, specific contracts were declared illegal, in the RPP case the SC declared the National Power Policy as a failure. The SC also came up with its own judicial economic analysis, declaring that the cost of production through RPPs was much higher, and that electricity can be produced at a cheaper cost by rectifying and developing the already installed electricity generation and distribution system. The articulation of an alternate economic policy is not just blatant disregard of the universally accepted norms of judicial conduct, but it is also unprecedented not only in Pakistan, but in almost all other jurisdictions. The NRO (National Reconciliation Ordinance) proceeding had one legal question; that is, whether the NRO was a valid piece of legislation or not. The Supreme Court wrote 290 pages, most of which had no connection with the question at hand. The implementation and contempt proceedings were completely without judicial precedent. In the implementation proceeding, the Court firstly avoided tackling the question of the immunity of the President under Article 248 (which is complete immunity, however one tries to look at the language). Secondly, a legal point was that the charge initially framed against PM Gillani did not include "scandalizing" the Court, yet the final judgment charged and convicted him for that. Thirdly, the court in the original judgment, which did not disqualify PM Gilani, constituted a seven member bench. This disqualification was subsequently enacted by a three member bench. This amounts to an overruling of the seven member bench by the three member bench; a legally and logically preposterous situation. Finally, the Court itself, by disqualifying the PM, rendered the Speaker of the National Assembly, whose prerogative it was alone, as redundant. That is right, our independent judiciary, which has never even given a single decision against a military dictator, dismissed a democratically-elected Prime Minister. The so-called 'memogate' saga was effectively the establishment's attempts to topple the civilian Government. The court was happy to oblige, by taking up the case. The basic legal problem in the Memo proceeding was that the CJ and the Court violated a universally established principle of Jurisprudence, generally called "Political question doctrine", which is a simple principle which establishes that the courts will not interfere in matters political, or in the case foreign policy etc. The Court obviously violated the principle of separation of powers, and attempted to bring about an institutional conflict. The Court expressed its opinion prematurely in the proceedings, and lowered any dignity that the judiciary was supposed to have by forming an unprecedented, high-powered commission (having three provincial Chief Justices) to beg and plead a foreign national, Mansoor Ejaz to present himself, who had no inclination of coming before them and never did. The role played by the SC in missing persons case is uncritically praised by the media and human rights activists, as the court is persistently pressing on security agencies for recovery of missing persons. However, apart from some high-minded talk, it has achieved very little. The Inspector General Frontier Core (FC) has routinely disregarded orders summoning him to court, without much concrete action by the CJ in response. It can starkly contrasted to the PM's contempt case, since the FC and the intelligence agencies have more blatantly and routinely violated orders of the court, yet still no contempt proceedings have been initiated against them. In the Asghar Khan case, the SC directed the Federal Government to take necessary action under the Constitution and law against Gen (Retd) Aslam Baig and Lt. Gen (Retd) Asad Durrani, for facilitating success of IJI over Pakistan Peoples Party by distributing funds and effectively rigging the 1990 elections. The Judgment left a lot to be desired, and the SC put the ball in the Government's court to take action against the ex-Generals while not articulating the specifics of any such action. This is in glaring contrast from the NRO case, as no implementation proceedings have been started for the Asghar Khan case. Finally, one of the most egregious examples of corruption, bias and mockery of justice was the case of the Chief Justice's own son. The CJ's son was publicly accused by a business tycoon of blackmailing him, both demanding and accepting money, lavish trips and gifts in exchange for favourable court decisions. The taking of suo motu notice of a case involving his son is "gross misconduct" irrevocably, and a direct violation of the code of conduct of Judges. This alone is grounds for a reference to the Supreme Judicial Council and removal from service. Furthermore, all governmental investigations were stopped, the independent anti-corruption watchdog was not allowed to complete investigation and in fact, months later, the NAB (National Accountability Bureau) chief was dismissed by the chief justice. The case quietly disappeared form the limelight, and to this day I am unaware as to what happened to the son of the Chief Justice. Even the Parliamentary Accounts Committee was banned from auditing judicial accounts. While the country celebrated the restoration of democracy, it mourned the loss of freedoms associated with democracy. Freedom of speech, a fundamental value which was promoted by the civilian Government, the Chief Justice attacked and repressed. Moreover the CJ banned any criticism of the judiciary in the media so he could not be held to account. Journalists, television channels and newspapers were hounded with costly contempt of court proceedings, if even a guest on a show said anything critical against the judiciary. Lawyers who challenged him had their law licences suspended and were left unable to earn a living. As Chief Justice Iftikhar Muhammad Chaudhry retires, he leaves the court with a sullied reputation once again. The Chief was restored, but when will justice be restored? If I had written on this subject while My Lord was still in office, I would have been charged with contempt of court, perhaps disqualified from running for elections and possibly imprisoned. How is it reasonable that in a country, purporting to be a democracy, I am not permitted to speak freely? Why, as a politician, should I be banned from expressing political opinions? Why, as a student of history, can I not present the facts as I see them, without fear of reprisal? The CJ often used the constitutional provision that makes it illegal for anyone to ridicule the judiciary as justification. The irony, of course, being that it was not the courts' critics, but the Chief Justice himself who brought the court into disrepute. The court can, and must, only maintain its legitimacy through the dispensation of justice, not by coercion and censorship. However, I am hopeful with the retirement of the infamous Chief Justice, Pakistan will not only have an independent judiciary but an unbiased one as well. Unlike Iftikhar Muhammad Chaudhry, the remaining Justices are the true heroes of the Lawyers' Movement. They joined the movement not because they were ousted from office, but because they believed in justice. They volunteered to resign for the greater good. They did all this without receiving the fame and the glory enjoyed by the Honourable Former Chief Justice. I am confident Pakistan will now get justice. I trust the constitution is now in safe hands. Perhaps the newly independent, and currently untainted, court would like to start by restoring the so-called PCO judges who were illegally removed? Surely they, along with the rest of Pakistan, deserve long awaited justice. wo jin k hont ki jumbish se, Those, who with a quiver of their lips wo jin ki aankh ki larzish se, Those, who with a flutter of their eyes qanoon badalte rehte hain, Change our laws aur mujhrim palte rehte hain, bread and shelter criminals in choroon kay sardaron se the leaders of these thieves insaaf kay pah're darn se the gate keepers of justice main baghi hoon main baghi hoon I am a reble, I am a reble jo chahe mujh pe zulm karo! Punish me as you wish

M WAQAR..... "A man's ethical behavior should be based effectually on sympathy, education, and social ties; no religious basis is necessary.Man would indeed be in a poor way if he had to be restrained by fear of punishment and hope of reward after death." --Albert Einstein !!! NEWS,ARTICLES,EDITORIALS,MUSIC... Ze chi pe mayeen yum da agha pukhtunistan de.....(Liberal,Progressive,Secular World.)''Secularism is not against religion; it is the message of humanity.'' تل ده وی پثتونستآن

Thursday, December 12, 2013

Joyless Justice: The Unhappy Legacy of Pakistan's Newly 'Independent' Judiciary

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment