M WAQAR..... "A man's ethical behavior should be based effectually on sympathy, education, and social ties; no religious basis is necessary.Man would indeed be in a poor way if he had to be restrained by fear of punishment and hope of reward after death." --Albert Einstein !!! NEWS,ARTICLES,EDITORIALS,MUSIC... Ze chi pe mayeen yum da agha pukhtunistan de.....(Liberal,Progressive,Secular World.)''Secularism is not against religion; it is the message of humanity.'' تل ده وی پثتونستآن

Monday, April 9, 2012

Why are English and American novels today so gutless?

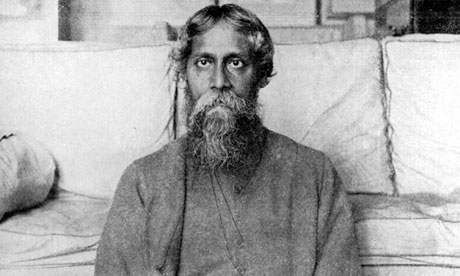

The great Bengali thinker Rabindranath Tagore

, born 150 years ago, was a passionate political author. Sadly, literary writers today seem to have no time for politics

The past sometimes shames us. At least, visitors this weekend to Dartington Hall in the south Devon town of Totnes must have come away feeling taunted by history. Because while the festival they attended was celebrating the life of Rabindranath Tagore, the great Bengali artist and thinker born 150 years ago, it also cast a shard of light on a gaping, and usually unremarked upon, hole in today's culture. You glimpsed it every time a musician performed one of Tagore's songs urging fellow Indians not to give up their struggle against British rule, and you confronted it directly in discussions of the poet's political and social campaigning. Because what his legacy draws attention to is a creature so rare in today's culture as to be semi-endangered: the political author.

Even the most casual acquaintance with Tagore's work cannot escape his politics. His novels attacked the oppression of women; his essays warned about environmental degradation; he argued with Gandhi about what an independent India should look like; and he delivered lectures in America on the evils of nationalism ("at $700 per scold", as one newspaper sniped). Nor was the poet all talk: a believer in educational reform, he established a school, then a university in the Bengali countryside. They have grown vastly since, although students reportedly still take their lessons sat under trees. Even the venue for this weekend's festival, Dartington Hall, was a 500-year old wreck – until a couple of western Tagoreans bought it and, at his urging, transformed it into a centre for learning and agricultural work and to reinvigorate an impoverished rural community.

The first Asian recipient of a Nobel prize for literature, Tagore was an exceptional figure – but he was not alone. Another Bengali, Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay, won huge success for his stories criticising India's caste and class system; while Mulk Raj Anand published novels titled Untouchable and Coolie. As for Tagore's western contemporaries, they were just as engaged with their politics and society. Spanish civil-war combatant Orwell is the most striking example, but there was also Spender, Auden and Pound.

Look for their equivalents in England or America now, and you'll be disappointed. Some politically committed authors immediately come to mind, such as Dave Eggers – for his novels on Sudanese refugees and post-Katrina New Orleans, and his establishment of children's reading groups – but the paucity of their number reinforces how few there are. India is subject to a similar lack: Arundhati Roy is the stand-out example of the author-turned-activist, but the fact that she has not written a novel after 1997's The God of Small Things suggests that she has traded fiction for campaigning.

Indeed, readers wanting fiction that offers up political or social commentary are hardly drowning in paperbacks. Plenty of authors can slip in cute references to the internet or the other stuff of everyday life. But what's striking about the novels that address themselves directly to society is how the authors often fail to sustain them as full-blooded fiction. Joshua Ferris' novel of office life, Then We Came to the End, and Gary Shteyngart's satire on consumerist America, Super Sad True Love Story, are both superb depictions of social landscapes for the first 100 pages or so. But in both cases it's as if delving into so much reality has tuckered out the authors and they have run out of energy to deliver an actual plot.

What I'm complaining about here is not just the lack of options on the three-for-two table. This is a time when, from the environment to the economy to the hollowing-out of so many public institutions, there are many big crises that need addressing – and not just by the desiccated imaginations of frontbench MPs or in 800-word columns. At the point when we need people of all disciplines and none to offer their say, the artists are missing. In the 1920s and 30s, Tagore helped place the perimeter on what would be possible in an independent India. In Britain or America or India today, our social boundaries are defined by the market and ever more diffident politicians.

Of course there are exceptions. In Scotland, James Robertson and Pat Kane and other artists do address themselves to national concerns. And in English theatre, such as the Tricycle or the National, audiences can still see openly political work. But English and American novels are particularly gutless.

Some of this is down to how economics and politics have been cordoned off from the rest of society: as stuff best left to the experts and the careerists. But literature too has been professionalised, so that authors now go from their creative-writing MAs to their novels to their relentless promotional work. Contemporary literary writers, it sometimes seems to me, are so tightly wedged behind their Apples that they have no time for politics. Unless you count signing the odd letter to the broadsheets as a political activity.

Yet the desire for a more imaginative politics hasn't gone away, as is clear from the Occupy movements or the student sit-ins, or the numbers that turn out on a Sunday morning in Totnes to listen to a talk about Tagore's activism.

In one of his most celebrated poems in Gitanjali, Tagore called for a country: "Where the mind is without fear and the head is held high/...Where the world has not been broken up into fragments/ By narrow domestic walls ... Where the clear stream of reason has not lost its way/ Into the dreary desert sand of dead habit." That warning against the comfort of small thinking remains relevant today.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment